If the less-is-more influence of mid-century Modernism will come to define the design of the previous decade, the 2020s is poised to be an era of experimentation. Some of the most exciting pieces earmarked for release in 2023 border on the downright esoteric. Clay-hewn coffee tables that resemble sculpture; chubby sofas in Pop Art-bright hues, cabinets glowing with traditional Japanese lacquer or the console made from dust sum up today’s pluralist, postmodern aesthetic.

What lies behind the change? Covid lockdowns, which gave makers time to reflect and innovate, could be one reason. Sustainability is another. As designers work to meet the expectations of more eco-minded buyers, that shift from linear to circular production is fuelling a mini renaissance in creativity — whether it is working with artisans to perpetuate traditions and ensure livelihoods, using natural or local materials or turning factory offcuts into objects of beauty.

Utilising technology to minimise energy and waste is another theme. At last year’s New Designers show of graduate talent in London, Tom Golland won the Conran Shop New Designers award for his neoclassical side table made from light, recyclable aluminium digitally printed to emulate marble.

There is a practical aspect to all this too. “Rising costs — of materials and shipping — are forcing makers to become more resourceful,” says Prince Jewiti, co-founder of Galerie Revel, a Bordeaux-based gallery for collectable contemporary design from France, South America, Africa and elsewhere. With an emphasis on novel use of materials and craftsmanship, it makes its debut at this year’s Collect craft fair at Somerset House.

At last winter’s Design Miami, an international fair for contemporary and vintage design, Sarah Myerscough, whose eponymous gallery champions high-end design, had to put up a barrier to stop crowds touching Christopher Kurtz’s drinks cabinet — a tactile, rippling version of traditional linenfold carving made from tulipwood — displayed on the Best of Show award-winning stand.

Myerscough, who will also be exhibiting at San Francisco’s FOG Design+Art fair later this month, singles out Marcin Rusak as another name to watch. The Polish designer’s tables and asymmetrical shelves are made from resin embedded with the silvery halos of decayed flowers — an oddly beautiful material which grew out of his experiments in horticulture.

Other makers to note include Peshawar-based Studio Lél, where Afghan refugees skilled in the ancient art of Pietra Dura work on contemporary furniture (sold on online gallery Adorno). British maker Max Lamb’s (represented by Gallery Fumi) Urushi wooden furniture collection is finished by lacquer craftsmen from Wajima, Japan using sap from the Urushi tree.

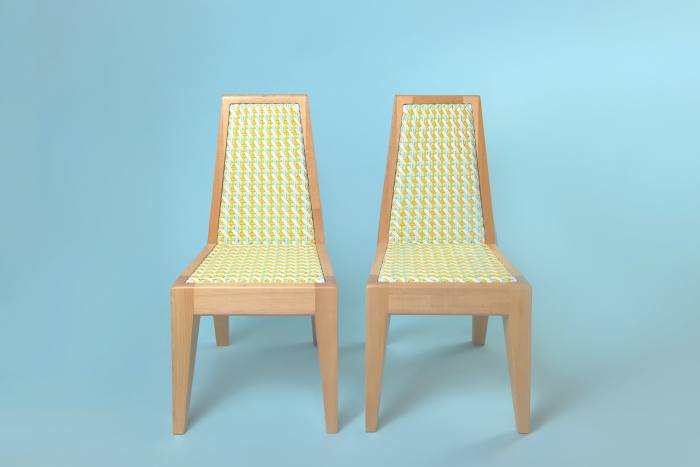

Formed in response to the country’s economic crisis, Beit Collective works with more than 60 artisans in Lebanon. Its Beiruti chair, featuring intricate Khayzaran cane-weaving, is a collaboration with dynamic London designer Adam Nathaniel Furman.

When London maker Jane Atfield turned discarded plastic sheets into lean-lined furniture 30 years ago, upcycling was a novelty. Now, thanks to the climate emergency and stuttering supply chains, it is a priority.

At the cutting edge of research are the makers repurposing natural detritus: architect Sara Abu Farha and engineer Khaled Shalkha turn surplus, UAE-sourced dates into a material called “datecrete” for their minimalist furniture, showcased at last year’s Dubai Design Week. Belgium-based Roxane Lahidji’s elegant tables, seats and lamps are made from tree resin mixed with sea salt for a surprisingly marble-like effect.

Then there are the designers finding new uses for industrial flotsam and jetsam — like modern alchemists. Charlotte Kidger turns recycled polyurethane foam dust — a byproduct of 3D model making — into tables or mirrors, the fragmented, jagged edges evoking the gravitas of ancient relics.

Korean maker Kwangho Lee, shortlisted for Wallpaper’s 2023 Designer of the Year, uses humble nylon rope for his hand-woven chunky benches and chairs. A collaboration with Swedish brand Hem has brought his experimental pieces to a wider audience.

A focus on sustainable materials has given rise to another movement — hyperlocalism, with makers foraging for found objects in their neighbourhoods while collaborating with nearby manufacturers. In London, Atelier 100 is an Ikea-backed project promoting makers who work with the capital’s factories, making use of discarded material for new pieces such as Mitre & Mondays’ floor lamp, a mix of timber, metal and the capital’s cobblestones.

In Newcastle, emerging maker Joe Franc’s stint working for a contract furniture manufacturer in Germany led him to question his role as a designer. Visits to sprawling commercial furniture fairs deepened his concern with the industry’s fixation with “squeaky-clean” newness.

It sent him back to his studio to focus on turning local street finds into practical, robust furniture: a chair made from wardrobe doors, a classic Windsor chair repurposed as a stool.

“As design students we’re taught to think in a linear fashion — working through a problem with a series of sketches before choosing the material,” he says. “We still want to make coherent, functional things, but perhaps it’s time to flip the way we do things by starting with the material and letting that dictate the outcome.” As our shortlist of other makers to look out for proves, it is, says Franc, a “thought-provoking time” to be a designer.

The House & Home shortlist

Agnes Studio

Guatemala-based Agnes Studio’s striking sculptural furniture grew out of a 2016 project sponsored by USAID, an international development agency. Creatives were asked to come up with ideas to bring the country’s craft traditions to a wider market.

“Typically, designers will tell artisans what to do. Our pitch focused on a meaningful dialogue, creating pieces that honour local traditions while also being contemporary,” says Gustavo Quintana-Kennedy, an architect who runs the studio with his wife Estefania de Ros, an interior designer.

Makers — sculptors, woodcarvers, metalworkers — use indigenous materials such as stone, bronze or wood. The asymmetrical hardwood surface of the Altar table, for instance, floats on bulbous legs carved from volcanic stone mimicking the contours of Mayan artefacts; the curved Lana chair is upholstered in white Highlands wool — like a shaggy embrace.

“This is slow furniture, with an artisanal soul, to hand down the generations,” says de Ros.

Marlène Huissoud

Growing up on a farm in the French Alps, where her parents kept bees, Marlène Huissoud became fascinated by the “habits of insects”. Her experimental and surreal furniture, exhibited at museums such as the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and MAK Vienna, aims to “bridge the gap between humans and nature” by incorporating insect waste into the designs.

For the surfaces of a slender-legged cabinet she used silkworm cocoons, sourced from a “slow” silk maker in India. (Conventional silk production involves boiling the cocoons during the pupal stage for speedier manufacturing; kinder methods allow the moths to develop and emerge from the cocoon.)

Huissoud’s cocoon-decorated surfaces are glazed in propolis, a resin-like material harvested annually from hives and used by the ancient Egyptians for mummification.

“Ultimately it’s about narrative: I want to push the boundaries of design by telling stories about the natural world,” says Huissoud, who dreams of owning her own “circular” farm, where she can plough back the natural waste into her designs: a haven for wildlife, bees and insect waste, “full of creative possibilities,” as she puts it.

Goldfinger

According to Grown In Britain, which promotes the use of indigenous wood, the UK imports £7.8bn of timber every year. Only China imports more. Goldfinger, a furniture design and making social enterprise tucked into the cavernous basement of Ernö Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower — hence the name — aims to change that.

Its quiet, Scandi-esque desks, chairs and bookcases are made from local wood such as plane or ash, felled due to disease or urban development, each piece stamped with the tree’s GPS co-ordinates. With clients who include interior designer Nicola Harding and architect Thomas Heatherwick, co-founder Marie Carlisle says her goal is to “bring luxury and sustainability together”.

The Goldfinger Academy runs free training programmes for aspiring makers, and North Kensington locals are invited to sit at the long trestle table for a monthly Sicilian lunch.

Zavier Wong

Styrofoam is the hidden ingredient of building materials: essential but rarely seen. Zavier Wong wants to elevate its reputation. The Eindhoven Design Academy graduate’s furniture is made from locally discarded polyurethane foam speckled with gold leaf — for a surprisingly expensive, Terrazzo-like look.

“Foam’s so cheap that anything not used is thrown away; I like the idea of turning a mass-produced material into something precious,” says the Eindhoven-based maker, who made his debut at last year’s PAD, a selling exhibition of antique and contemporary design in London. He uses simple cutting and gluing techniques to sculpt his pieces — tables, stools, benches — which are sealed with resin and polished for a lustrous finish.

Foam, says the reflective maker, has become a “metaphor for exploring ideas . . . I was born in Singapore, a very industrialised, uniform place; my work is partly a reaction to that because each piece is slightly different.”

Andu Masebo

Seeking inspiration for his next project, Andu Masebo spotted a stack of metal tubes in his workshop. “I sent them to local garages asking them to spray them in whatever colour they were using that day,” says the Royal College of Art graduate.

The resulting side tables — an animated, asymmetrical mix of wood with brilliant red and silver legs — led to another “hyperlocal” piece. A curvy-framed chair fabricated from bent car exhausts with a squashy recycled rubber seat was selected by the design incubator Atelier 100, set up to promote London makers working with local materials.

“So much of what I do is about resourcefulness, capitalising on what’s to hand,” says Masebo, citing his graduate project: a chair made out of a single piece of wood, cut into positive and negative shapes that slot together tidily — like a jigsaw — to minimise waste.

Matang

Lucien Dumas and Lou-Poko Savadogo, of Paris-based design and architecture practice Matang, are architects who also studied at the capital’s École Boulle college of fine arts and crafts (Savagado focused on tapestry and Dumas cabinet making).

Their joint skills are expressed in furniture that is handmade — and cerebral. Natural materials combined with classical techniques give the designs, prototyped by hand in the studio, an ageless feel.

A coffee table features a surface of smooth lava stone from Auvergne; the wooden base is bound in rope dyed with turmeric — a recurring motif. Their Burnt Cedar cabinet (at Galerie Revel), made without screws or nails, was inspired by the Japanese technique of shou sugi ban, which weatherproofs architectural cladding by charring its surface.

As Dumas puts it: “We consider pieces of furniture as elements of architecture; they are constructed, structured and assembled in the same way that a building might take shape.”

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @FTProperty on Twitter or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram